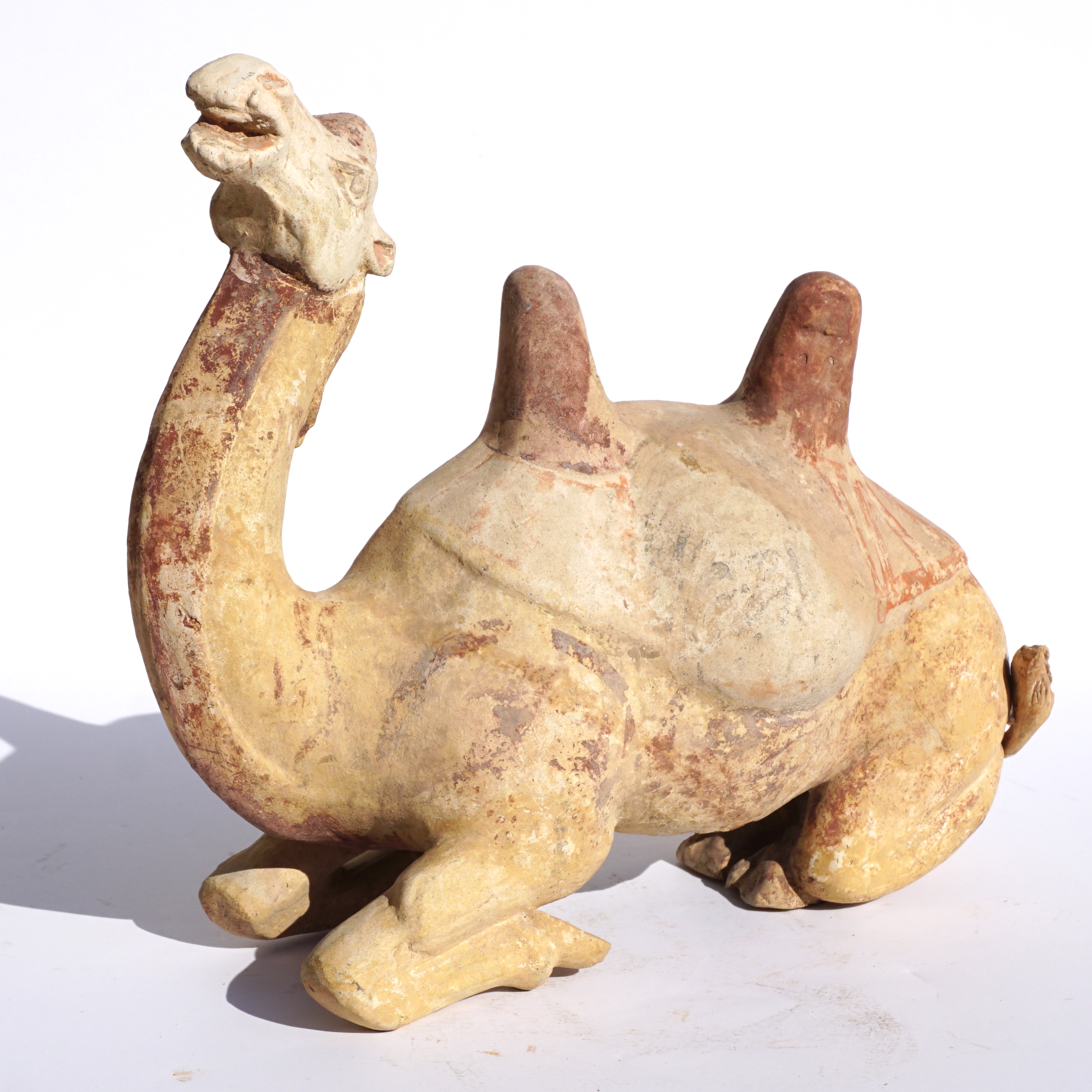

Description

A recumbent Bactrian camel resting on folded legs, with remnants of polychrome slip evident. The character or this sculpture is amazing. Terracotta, 618 AD to 906 AD. COA.

Measures: Height 10 inches, width 11 inches, depth 4 inches.

Condition: Excellent. No repairs detected.

Provenance: From the Private collection of Morton & Kathleen Sachs of Louisville, Kentucky acquired from TK Asian Antiquities (Williamsburg, VA) in 2000.

It was during the Tang dynasty that China’s outstanding technological and aesthetic achievements opened to external influences, resulting in the introduction of numerous new forms of self-expression, coupled with internal innovation and considerable social freedom. The Tang dynasty also saw the birth of the printed novel, significant musical and theatrical heritage and many of China’s best-known painters and artists.

The dynasty was created on the 18th of June, 618 AD, when the Li family seized power from the last crumbling remnants of the preceding Sui Dynasty. This political and regal regime was long-lived, and lasted for almost 300 years. The imperial aspirations of the preceding periods and early Tang leaders led to unprecedented wealth, resulting in considerable socioeconomic stability, the development of trade networks and vast urbanisation for China’s exploding population (estimated at around 50 million people in the 8th century AD). The Tang rulers took cues from earlier periods, maintaining many of their administrative structures and systems intact. Even when dynastic and governmental institutions withdrew from management of the Empire towards the end of the period, their authority undermined by localised rebellions and regional governors known as jiedushi, the systems were so well- established that they continued to operate regardless.

The artworks created during this era are among China’s greatest cultural achievements. It was the greatest age for Chinese poetry and painting, and sculpture also developed (although there was a notable decline in Buddhist sculptures following repression of the faith by pro-Taoism administrations later in the regime). It is disarming to note that the eventual decline of imperial power, followed by the official end of the dynasty on the 4th of June 907, hardly affected the great artistic turnover.

During the Tang dynasty, restrictions were placed on the number of objects that could be included in tombs, an amount determined by an individual’s social rank. In spite of the limitations, a striking variety of tomb furnishings, known as mingqi, have been excavated. Entire retinues of ceramic figures, representing warriors, animals, entertainers, musicians, guardians and every other necessary category of assistant, were buried with the dead in order to provide for the afterlife. Warriors (lokapala) were put in place to defend the dead, with domestic servants and attendants, and officials to run his estate in the hereafter. Charming examples of animals such as the current piece are perhaps the most amusing and aesthetically-pleasing of the mingqi, however. This attractive sculpture is an eloquent reminder of China’s outstanding heritage, and a beautiful addition to any serious Chinese collection.